King memorial idea was born in Silver Spring

Brother Hatchel doesn’t see so well anymore. And he has a prosthetic leg. So brothers Navy and Klugh guide him along the outdoor railing of the historic school where their fraternity chapter meets.

Using two canes, Hatchel, 74, who is wearing his black-and-gold Alpha Phi Alpha ball cap, maneuvers down the walkway, with Navy, 76, and Klugh, 74, guiding him: Turn right, careful, watch your step.

The three Silver Spring men have been “brothers” most of their lives — members of the same elite black fraternity as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. And as they anticipated the dedication of the $120 million King memorial , they were proud to point out that the idea was born in a modest brick rambler on East-West Highway.

Thursday night, officials announced that because of Hurricane Irene, the dedication of the memorial will take place not on Sunday as expected, but in September or October.

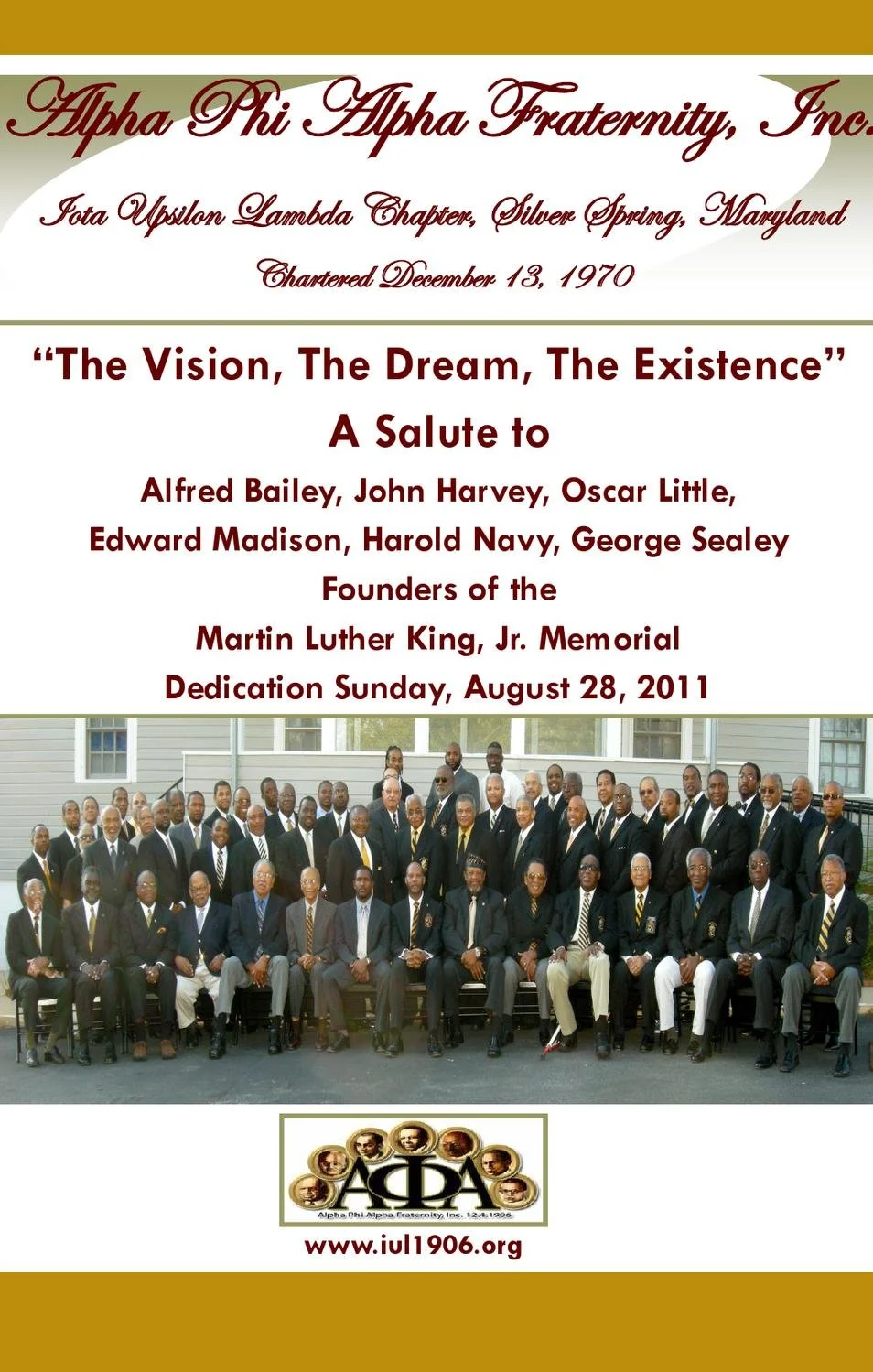

In 1984, members of the local Alpha chapter — Iota Upsilon Lambda — hatched the plan for what has become the granite memorial at the Tidal Basin.

There, over coffee in the dining room of an Alpha member and American diplomat named George H. Sealey Jr., a half-dozen chapter members asked the question: Why not a memorial to King on the Mall?

Now, 27 years later, as the idea bears fruit, only two of the original six are alive. Many of the chapter brothers of that generation — men who grew up with segregation and who guided the fledgling project — are elderly and frail.

But this month, sitting at a table in their meeting hall, Robert Hatchel, a retired school principal, Harold Navy, a retired architect, and Andrew Klugh, a retired government mathematician, recalled how the plan began and the early obstacles it faced.

Navy is one of the two living original planners, according to the three men and the fraternity. The other is Eddie L. Madison Jr., a former government and communications executive, who lives in Eugene, Ore.

The others, in addition to Sealey, were Alfred C. Bailey, Oscar Little and John Harvey.

The gathering place was Sealey’s dining room.

“We used to meet like twice a month,” Navy said. “We would all come in after dinner, and we would have coffee. . . . We started, and every month we would make some progress. It was like a stepping ladder.”

“We had never had a black honored on the Mall,” he said. “Here was Martin Luther King, in our generation. We thought this was a man that was a quality individual that had given his life to try to have betterment of the races.”

In addition, King had been a member of Alpha Phi Alpha. “That was another motivational step for us,” Navy said. “It was a brother that we want to see honored.”

Alpha Phi Alpha is the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans. It was founded at Cornell in 1906 and is open to qualified applicants long after they have left college. It was Alpha Phi Alpha that created the foundation that went on to build the memorial.

Navy and Klugh were Alphas when they attended the 1963 March on Washington and had heard King deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Navy was one of the spectators who climbed a tree along the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool to get a better view. “I had never seen such a crowd in my life before,” he recalled.

Klugh said: “I came back from that march so pumped up and so proud to be an American that particular day. It was amazing.”

Sealey, who died in 2004 at age 82, was a World War II veteran, a member of the Peace Corps and the Foreign Service, and a man of ideas.

“George came up with the idea” for the memorial, Klugh said. “He started talking to people, and as it began to mushroom he brought other people in, like brother Navy here and others, to be a part of that group.”

Later in 1984, the chapter brought the idea to an Alpha convention in Cleveland.

“The membership didn’t support it initially,” said the fraternity’s current general president, Herman “Skip” Mason Jr. “Because it was a really ambitious project.”

But after gaining broader support, the fraternity embraced it. “Then it began to take a life of it’s own,” he said.

And always behind it stood the brothers of Iota Upsilon Lambda.

The chapter was formed in 1970 and it won the chapter-of-the-year award seven times in a row. “We had a lot of independent thinkers,” Navy said. “We were taught as young brothers, ‘There’s nothing you can’t do.’ ”

Still, some of the men had doubts about the memorial. “I didn’t know what would happen,” Hatchel said.

Navy said he never doubted, but also never expected a memorial so huge it’s “a shocker.”

“Here is a man we honored, and we started years ago trying to make it happen,” he said. “I did not ever think we would have something so grandiose with such a permanent location,” and not far from where he watched the King speech from a tree almost 50 years ago.

All three men have visited the memorial. Hatchel has felt the rough surface, and chief architect Ed Jackson Jr., also an Alpha, described the memorial for him.

“It’s kind of like, ‘Pinch me,’ ” Hatchel said. “I don’t feel like it’s really true, but it is.”